In a class I was teaching at a non-LDS university on Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o classic novel, Weep Not, Child, I asked students what most stood out to them about the book. One student responded: “One of the men had two wives…” and paused for a moment.

“And…”

“ONE OF THE MEN HAD TWO WIVES!”

The phrase rang in her ears.

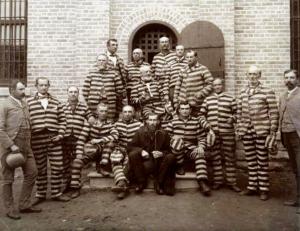

While not news to most, the LDS Church has recently published a series of three essays (see here, here, and here) that illustrate how Joseph Smith and the nineteenth-century LDS community engaged in a three-generations-long experiment in polygamy, an experiment that led the Saints headlong into a federal war with the American government. It was an experiment that won the Saints the undying hatred of the Western world and the affection of African observers an ocean away who cheered as the Saints refused to give up polygamy, even long after they issued a Manifesto saying that they would—a point amply made in the third essay. As one Nigerian news editor observed in 1897, the Mormons gave hope to Nigerian polygamists fighting British colonial efforts to suppress their marriage systems: “If it is impossible to suppress that view of marriage among a highly cultivated people not born under the system, but adopting it from conviction and preference, why should it be supposed that it among a people born to it and who for thousands of years have practiced it with wholesome results” (“The Marriage Question in the State of Utah United States of America,” Lagos Weekly Record, December 18, 1897). The editor’s hope proved to be misplaced, as the Saints gave up the practice for good seven years later in 1904. The American government had won.

Indeed, in an African context, polygamy has not been unusual, a fact not lost on nineteenth-century critics of Mormonism. In fact, this often served as the first point of attack: polygamy was evidence Mormons’ un-American qualities. As far as Eastern non-Mormons were concerned, polygamy transformed Mormons from an already-strange white sect into a geographic anomaly, a racial Other in a land increasingly dominated by white Anglo-Saxon Protestants. By adopting a practice that even the highest court of the land attacked as “Oriental,” Mormons had given up their claims to being respectable white Americans. Who knew what they were? Chinese, perhaps? Africans? Nobody knew exactly—except that Mormons weren’t white. And that’s what mattered.

So here we are in a 2014 LDS global faith community, recognizing that the history of this “American religion,” as Leo Tolstoy styled it, is inextricably interwoven with an institution that most have considered to be at odds with what America is about. Whether we are talking about the family of Victorian America or Cold War America, the model home has been envisioned as a husband and wife reigning as kings and queens of their respective households.

I have enjoyed the luxury of divorcing myself from polygamy at any point in my upbringing. All branches of my family tree bore its marks, and I am its direct offspring. To do so would have required a kind of massive denial along the order of tribal hatred. And in the Stevenson family, the motto has been: “Be true to yourself and your tribe.”

The essays now published force us to reckon with what plural marriage looked like on the ground, as it was practiced. While the writing of the essays are crisp, the lived reality was not. Joseph Smith was sealed to women who were married to other men. His wives included women as old as 56 and as young as 14. And his wife, his “beloved Emma,” did not always know about them. Various analyses have shed considerable light on the documentation undergirding the practice. Todd Compton’s seminal work, In Sacred Loneliness, became one of the first comprehensive treatments of Joseph Smith’s plural wives. Thanks to the archival digging spearheaded by Brian Hales, we know more than ever before about the polygamy’s paper trail. In his book, In Heaven as it is on Earth, Samuel M. Brown, the talented historian (who moonlights as a surgeon at the University of Utah) has cast plural marriage in the context of the Mormon hope of creating a “enduring community” of filial relationships that could transcend death. Kathryn Daynes’ work, More Wives Than One: The Transformation of the Mormon Marriage System, 1840-1910 shows how polygamy functioned in the Mormon community in Manti, using detailed demographic data culled from census records. So Latter-day Saints need not throw up their hands in an existential fit of agnosticism. Records, we have. The question is whether we want to look them in the eye or not. Choosing not to acknowledge one’s past does not make someone a bad person—just an intellectually unhealthy one.

So to the Saints who have, like my student, felt disgusted and shocked at Mormonism’s polygamist past, there are people here who are happy to help you carry the burden of history, hoping (praying, even) that in the carrying, we become more intellectually honest, more authentic, and more sympathetic as we look upon our forbearers who were ready to defy everything every value they held sacred as a sacrifice to the building of Zion in the wilderness.

~Russell Stevenson, The Mormon History Guy

Russell Stevenson has published two books, Black Mormon: The Story of Elijah Ables (2013) and For the Cause of Righteousness: A Global History of Blacks and Mormonism (forthcoming). He has also published in the Oxford University Press American National Biography series, the Journal of Mormon History, and Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought.

I wonder if African mormons will start wanting to be polygamously sealed in countries where it is legal…